Rating: 5/5

My description of this book in 10 words or less : A rare gem of a book!

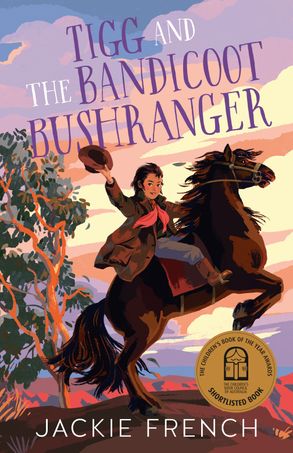

For ages: 6-10 years and up

Genre: Junior Fiction, Fable

Warnings : none

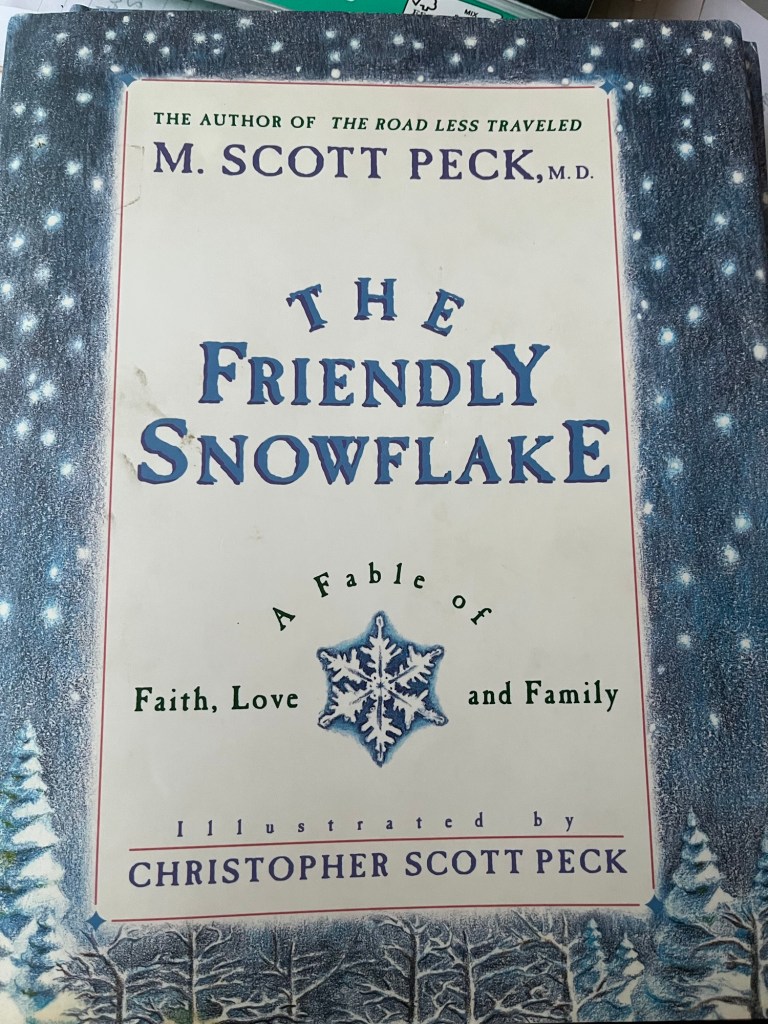

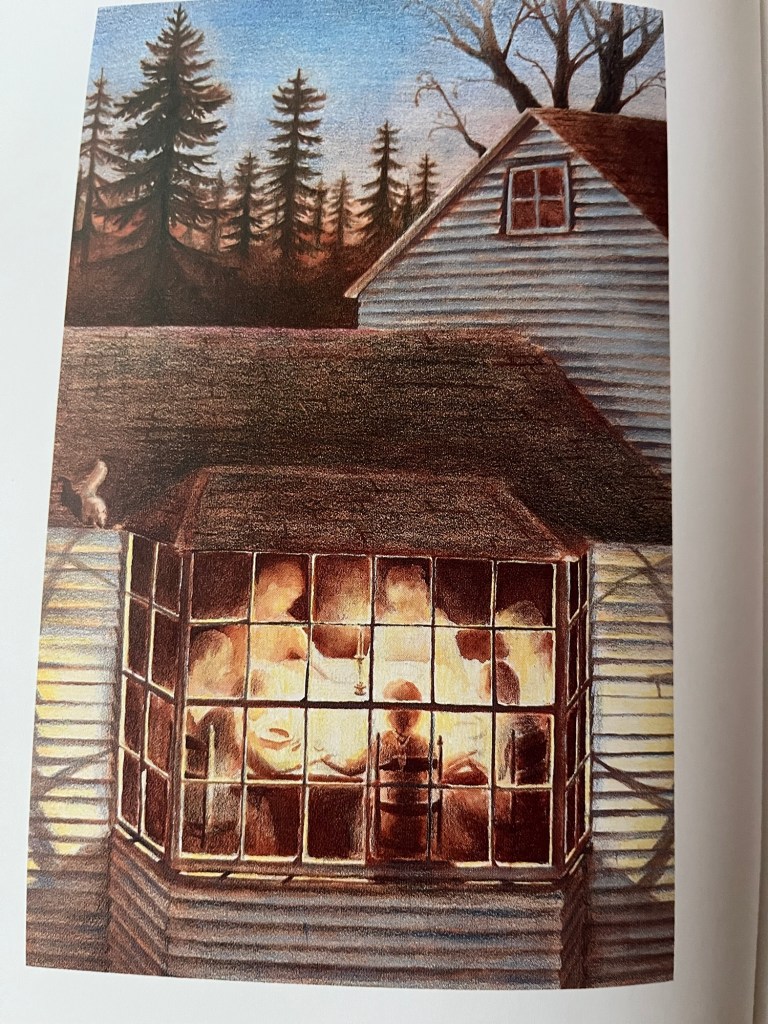

‘The Friendly Snowflake’ by M. Scott Peck is a fable for children about faith, love and family. When it was first published in 1992 it sold 155,000 copies. It is now out of print but I think it has a lot to offer. If you are a parent you may like to purchase a second-hand copy for your child online. The story is illustrated by M. Scott Peck’s son, Christopher Scott Peck.

Author Scott Peck commented that he wrote the story in response to parents who asked him: ‘what should I do for the spiritual education of my children?

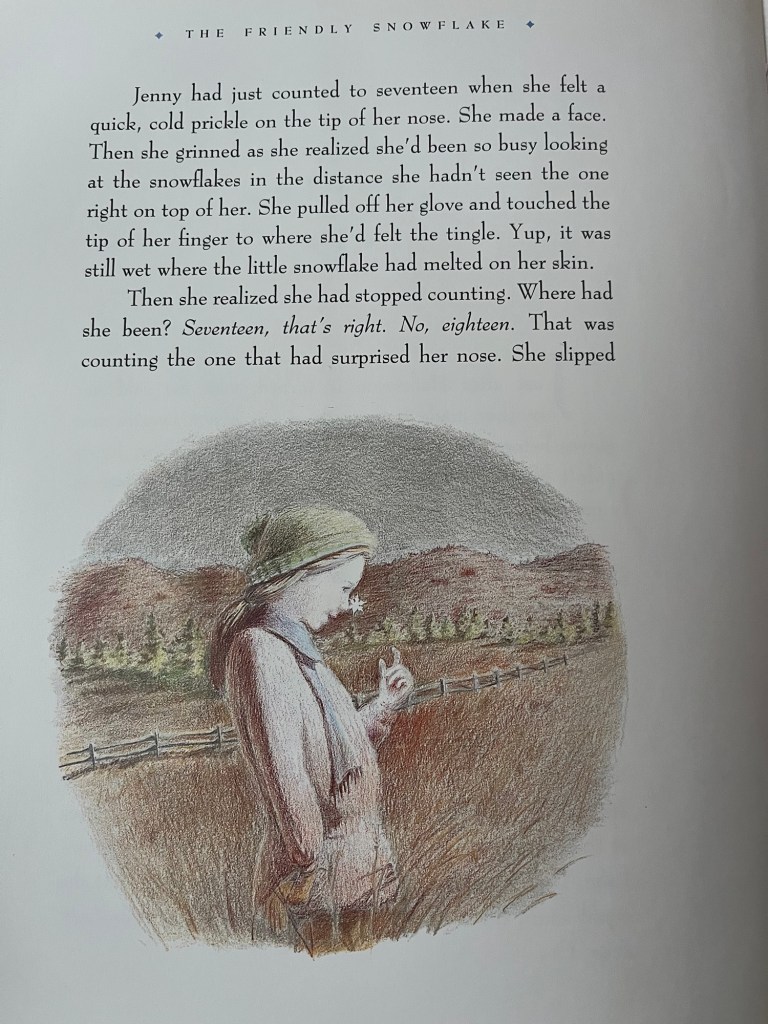

The story : A young girl ruggs up and ventures out into the snow to play. Whilst enjoying the day a snow flake happens to falls on the tip of her nose.

She gives the snowflake the name “Harry” and sees it as ‘a friendly snowflake.’

She counts the number of snowflakes that fell and, finding there were only a few, asks what were the chances of that particular snowflake falling just on her nose at that time :

“Since there were so few snowflakes, wasn’t it something that one of them had managed to find its way right to the tip of her nose …Why? Maybe it had wanted to meet her. Maybe it was a friendly snowflake.” (p.11)

“That’s silly”….said her brother. “Snowflakes aren’t friendly….They just land where they land. It was an accident…just a statistical happening.” (p.12)

Their Mother ends the first ‘discussion.’ hinting that neither child has enough evidence to go on to win the argument. So they leave that one go. However, the Mother says that it can be ‘very important sometimes to decide whether something’s an accident or whether there’s meaning behind it.” (p.13)

An interesting thought in a world that always seems to demand strictly factual cause and effect answers. The Mother’s statement sows the seed of thought for the rest of the story.

The girl’s brother is said to be interested in science due to his Father who is a good role model. Her brother is reasonable and debates his sister in a reasonable manner. Although he cannot see the value of her arguments, he opens a book and shows her what snowflakes look like under the microscope. He is willing to talk and debate even if he doesn’t at first agree.

The ongoing discussions about spirituality, the soul, snowflakes, serendipity and whether things happen for a reason or not make for a fascinating read.

What follows is a quite amazing series of debates between the children about whether the snowflakes clump together because they are ‘…related like a family’, or whether they ‘just happen to be next to each other in the air.’ Jenny persists with her argument that it is theoretically possible that the snowflakes are ‘related, like a family’.

She brings the debate to the fact she is close to her brother in the same living room and that is no ‘accident.’ However, her brother still doesn’t get her argument, and she privately regrets that anything he cannot explain he always seems to say is ‘an accident.’

A strength of the book is that it shows how to argue purposefully and rationally in support of things that are difficult to prove. It is a hopeful book which hints at the value of mystery and the fact that not everything can be explained.

For those readers who want to listen, there is much here to ponder on.

Here is one of my favourite quotes from the book:

“She wondered…God was certainly good to them. But did God actually love her? He -or She- was important and powerful. How could God possibly care for just one person, particularly for a person as small and ordinary as herself? But then she remembered Harry (the snowflake.). Harry had gone to the trouble to find her. Maybe God was like that. …maybe God could somehow be both in a giant storm and in a single little snowflake…” p.30